The Minority Government of Isabella II (

Spanish: ''Isabel II''; 10 October 1830 – 9 April 1904) is the period in the history of Spain during which

Isabella II

Isabella II ( es, Isabel II; 10 October 1830 – 9 April 1904), was Queen of Spain from 29 September 1833 until 30 September 1868.

Shortly before her birth, the King Ferdinand VII of Spain issued a Pragmatic Sanction to ensure the successi ...

, after the death of her father

Ferdinand VII of Spain

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Charles IV of Spain

, mother = Maria Luisa of Parma

, birth_date = 14 October 1784

, birth_place = El Escorial, Spain

, death_date =

, death_place = Madrid, Spain

, burial_p ...

, reigned; first under the

regency

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

of her mother

Maria Christina of the Two Sicilles and then under

General Baldomero Espartero, covering almost ten years of her

reign

A reign is the period of a person's or dynasty's occupation of the office of monarch of a nation (e.g., Saudi Arabia, Belgium, Andorra), of a people (e.g., the Franks, the Zulus) or of a spiritual community (e.g., Catholicism, Tibetan Buddhism ...

, from September 29, 1833, until July 23, 1843, when Isabella was declared of age.

Upon the death of

Ferdinand VII on September 29, 1833, his wife,

Maria Christina, immediately assumed the regency on behalf of her daughter,

Isabella II

Isabella II ( es, Isabel II; 10 October 1830 – 9 April 1904), was Queen of Spain from 29 September 1833 until 30 September 1868.

Shortly before her birth, the King Ferdinand VII of Spain issued a Pragmatic Sanction to ensure the successi ...

, and promised the liberals a policy different from that of the deceased king. Part of the Spanish society was expectant before a possible change in the

reign that was beginning and that would incorporate to the country the liberal models that were developed in some nations of

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

. The

First Carlist War

The First Carlist War was a civil war in Spain from 1833 to 1840, the first of three Carlist Wars. It was fought between two factions over the succession to the throne and the nature of the Spanish monarchy: the conservative and devolutionist ...

and the confrontations between the liberals of the

Moderate Party

The Moderate Party ( sv, Moderata samlingspartiet , ; M), commonly referred to as the Moderates ( ), is a liberal-conservative political party in Sweden. The party generally supports tax cuts, the free market, civil liberties and economic ...

and those of the

Progressive Party culminated in the rise to the

Head of State

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and ...

of General

Baldomero Espartero

Baldomero Fernández-Espartero y Álvarez de Toro (27 February 17938 January 1879) was a Spanish marshal and statesman. He served as the Regent of the Realm, three times as Prime Minister and briefly as President of the Congress of Deputies ...

during the minority of the future queen,

Isabella II

Isabella II ( es, Isabel II; 10 October 1830 – 9 April 1904), was Queen of Spain from 29 September 1833 until 30 September 1868.

Shortly before her birth, the King Ferdinand VII of Spain issued a Pragmatic Sanction to ensure the successi ...

, in a convulsive period plagued by governmental crises and social instability.

The situation in Europe

In

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

,

William IV

William IV (William Henry; 21 August 1765 – 20 June 1837) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death in 1837. The third son of George III, William succeeded h ...

initiated profound liberal reforms and

Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

became the real political engine of the country's life. After the defeat of

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

in the

Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar (21 October 1805) was a naval engagement between the British Royal Navy and the combined fleets of the French and Spanish Navies during the War of the Third Coalition (August–December 1805) of the Napoleonic Wars (1 ...

, the extension of what would soon become the

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

began to take shape, especially from 1837 with the accession of

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

to the throne.

Democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose g ...

was established in the country as an unquestioned model.

On the continent, with the dissolution of the

Holy Alliance

The Holy Alliance (german: Heilige Allianz; russian: Священный союз, ''Svyashchennyy soyuz''; also called the Grand Alliance) was a coalition linking the monarchist great powers of Austria, Prussia, and Russia. It was created after ...

in 1830,

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

had overthrown

absolutism

Absolutism may refer to:

Government

* Absolute monarchy, in which a monarch rules free of laws or legally organized opposition

* Absolutism (European history), period c. 1610 – c. 1789 in Europe

** Enlightened absolutism, influenced by the En ...

with the fall of

Charles X

Charles X (born Charles Philippe, Count of Artois; 9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836) was King of France from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. An uncle of the uncrowned Louis XVII and younger brother to reigning kings Louis XVI and Lou ...

and established a

constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

in the person of

Louis-Philippe d'Orleans, under whose rule the

industrial revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

was launched and the

bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. They ...

took the reins of the national economy.

Absolutism is relegated to

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

,

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

and

Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, although in the former the impulses of unification with the

German Customs Union

The (), or German Customs Union, was a coalition of German states formed to manage tariffs and economic policies within their territories. Organized by the 1833 treaties, it formally started on 1 January 1834. However, its foundations had b ...

, nourished by the liberals, who will not cease to obtain partial successes in the commercial field, will open the borders and will procure advances in the new pre-industrial society.

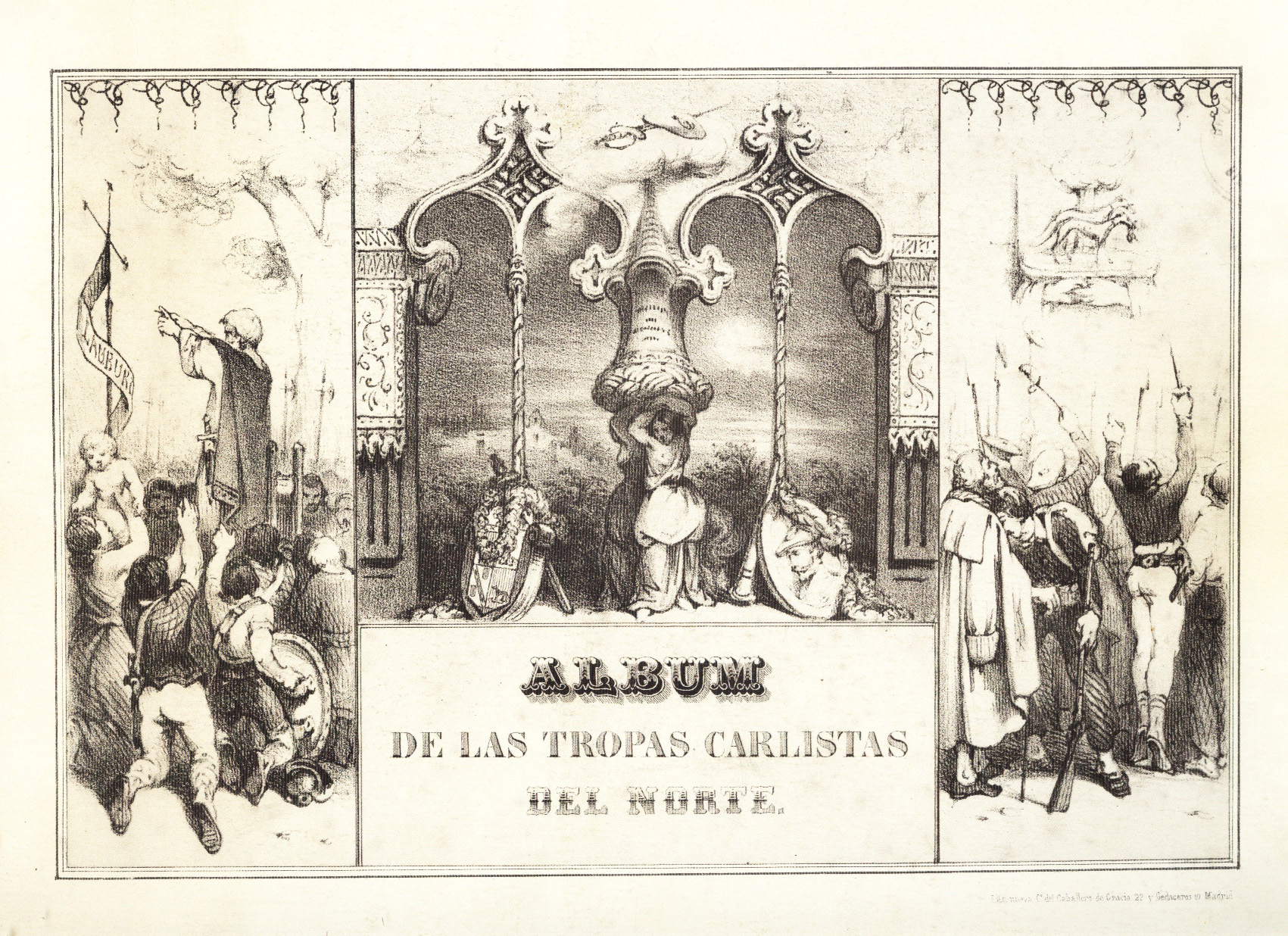

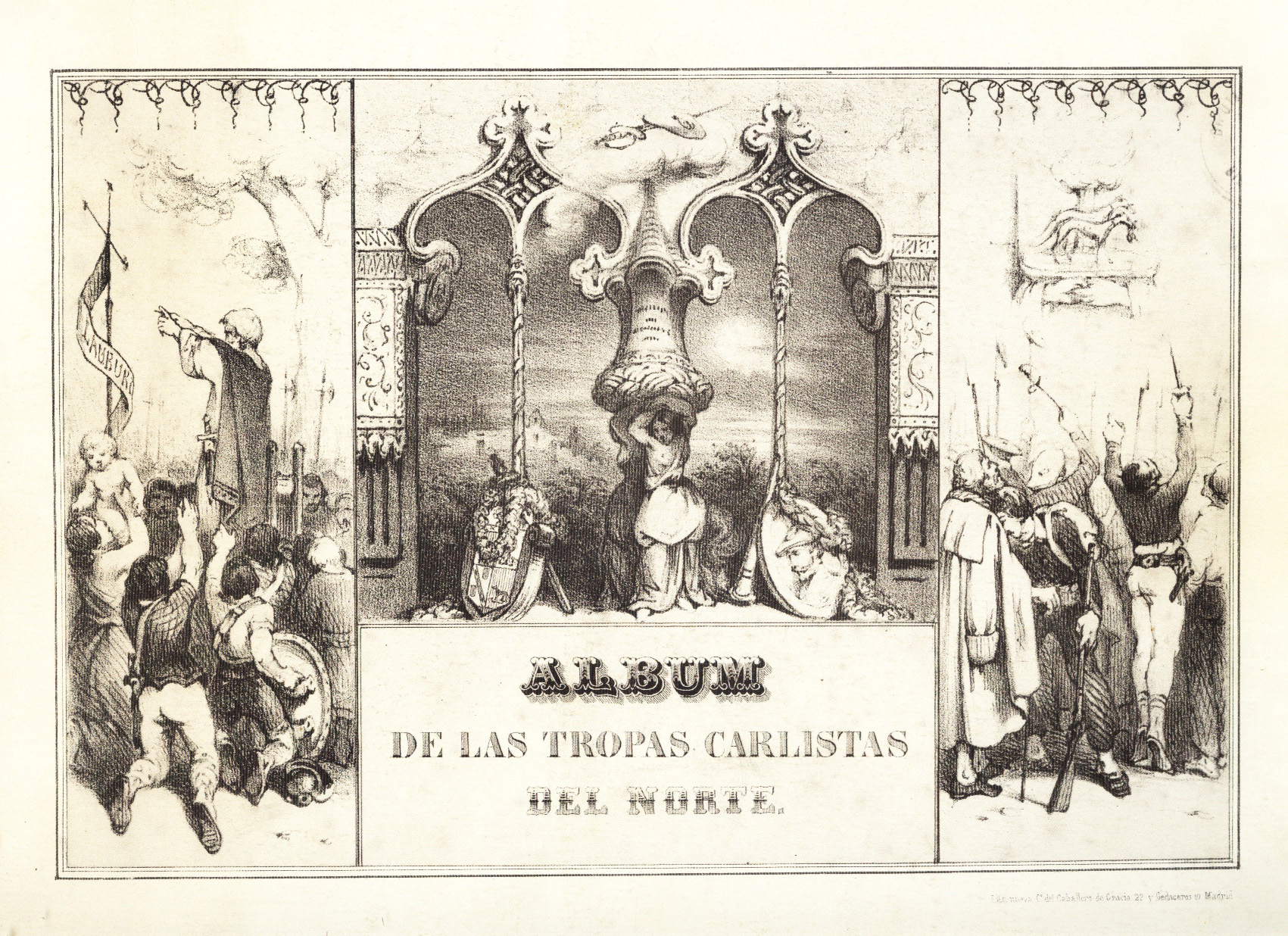

The First Carlist War

The death of

Ferdinand VII provoked a series of uprisings and the proclamation of

Don Carlos

''Don Carlos'' is a five-act grand opera composed by Giuseppe Verdi to a French-language libretto by Joseph Méry and Camille du Locle, based on the dramatic play '' Don Carlos, Infant von Spanien'' (''Don Carlos, Infante of Spain'') by Friedri ...

as

king

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

. The uprisings were led by absolutist military men who had been retired from the army or even prosecuted. The first to rise up was Manuel Martín González, followed by Verasategui, Santos Ladrón and

Zumalacárregui. A bloody

civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

began, characterized by its scarce geographical location, since it took place in the

Basque Country and

Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

and in some small pockets in

Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

,

Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to sou ...

and

Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, Valencia and the Municipalities of Spain, third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is ...

.

The sides

Broadly speaking, the

First Carlist War

The First Carlist War was a civil war in Spain from 1833 to 1840, the first of three Carlist Wars. It was fought between two factions over the succession to the throne and the nature of the Spanish monarchy: the conservative and devolutionist ...

can be defined as the means to decide the continuity of the

Ancien Régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for "ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

or the triumph of

liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

.

Carlism

Carlism ( eu, Karlismo; ca, Carlisme; ; ) is a Traditionalist and Legitimist political movement in Spain aimed at establishing an alternative branch of the Bourbon dynasty – one descended from Don Carlos, Count of Molina (1788–1855) – ...

defends

absolutism

Absolutism may refer to:

Government

* Absolute monarchy, in which a monarch rules free of laws or legally organized opposition

* Absolutism (European history), period c. 1610 – c. 1789 in Europe

** Enlightened absolutism, influenced by the En ...

. Among its ranks are the low rural nobility, the low Basque clergy and Basque and Navarrese peasants. The

Carlists unite under the cry of "God, Country and Fueros" (

Spanish: ''"Dios, Patria y Fueros"'') (the defense of the Fueros begins in 1834 by means of an imposition of the

Deputation of Biscay (

Spanish: ''Diputación foral de Vizcaya'') to

Don Carlos

''Don Carlos'' is a five-act grand opera composed by Giuseppe Verdi to a French-language libretto by Joseph Méry and Camille du Locle, based on the dramatic play '' Don Carlos, Infant von Spanien'' (''Don Carlos, Infante of Spain'') by Friedri ...

).

The

liberals are led by the queen regent

Maria Christina. At first they were moderate liberals, but later there were also

progressives

Progressivism holds that it is possible to improve human societies through political action. As a political movement, progressivism seeks to advance the human condition through social reform based on purported advancements in science, techno ...

. The enlightened middle classes, who had to put an end to the

Ancien Régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for "ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

, could be considered

liberals.

The development of the war

The Carlist uprisings of 1833 are followed by the creation of juntas or local governments. When

Don Carlos

''Don Carlos'' is a five-act grand opera composed by Giuseppe Verdi to a French-language libretto by Joseph Méry and Camille du Locle, based on the dramatic play '' Don Carlos, Infant von Spanien'' (''Don Carlos, Infante of Spain'') by Friedri ...

returned to

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

in 1834, he tried to create a government with the

General State Administration

The General State Administration ( es, Administración General del Estado) is one of the Public Administrations of Spain. It is the only administration with powers throughout the national territory and it is controlled by the central government.

...

in the

Basque Country and

Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

that would become the national government at the end of the War. The

Carlists used

guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or Irregular military, irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, Raid (military), raids ...

because of their knowledge of the rural environment and because the cities were liberal. The

First Carlist War

The First Carlist War was a civil war in Spain from 1833 to 1840, the first of three Carlist Wars. It was fought between two factions over the succession to the throne and the nature of the Spanish monarchy: the conservative and devolutionist ...

is a rural-urban confrontation that has three stages, of two years each:

*

1st stage (1833-1835): it is dominated by

Zumalacárregui, a Carlist. The liberal army is depleted by the guerrillas, which forces

Maria Christina to call up the progressives.

Don Carlos

''Don Carlos'' is a five-act grand opera composed by Giuseppe Verdi to a French-language libretto by Joseph Méry and Camille du Locle, based on the dramatic play '' Don Carlos, Infant von Spanien'' (''Don Carlos, Infante of Spain'') by Friedri ...

considers in 1835 the assault of

Bilbao

)

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize = 275 px

, map_caption = Interactive map outlining Bilbao

, pushpin_map = Spain Basque Country#Spain#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption ...

, but Zumalacárregui does not support this plan because he knows that the Carlist artillery would not withstand a siege. In the end the assault was a failure and Zumalacárregui died.

*

2nd stage (1835-1837): Zumalacárregui is replaced by

Cabrera. Both sides opted for control.

Luis Fernández de Córdoba

Luis Fernández de Córdoba (February 1555 – 26 June 1625) was a Roman Catholic prelate who served as Archbishop of Seville (1624–1625), Archbishop of Santiago de Compostela (1622–1624), Bishop of Málaga (1615–1622), and Bishop of Sala ...

, liberal, tries to create a line of containment to isolate the Carlists, but this line would oblige to cover more than 500 km (kilometers), an area too extensive. The Carlists try to relieve the pressure in the

Basque Country and

Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

with operations in

Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

and

Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to sou ...

, although they do not succeed and the rest of the war is only fought in the Basque Country and Navarre.

*

3rd stage (1837-1839): from 1837 the war is practically decided in favor of the liberals. Within the Carlist side a division arose between those who opted to surrender and sign the peace; and the intransigent ones who wanted to continue fighting. In the end,

General Maroto agreed with the liberals the

Convention of Vergara

The Convention of Vergara ( es, Convenio de Vergara, eu, Bergarako hitzarmena), entered into on 31 August 1839, was a treaty successfully ending the major fighting in Spain's First Carlist War. The treaty, also known by many other names includi ...

in August 1839, which put an end to the war, although Don Carlos would continue fighting for a few more months. Besides the peace, the agreement assures the continuity of the

Fuero

(), (), () or () is a Spanish legal term and concept. The word comes from Latin , an open space used as a market, tribunal and meeting place. The same Latin root is the origin of the French terms and , and the Portuguese terms and ; all ...

s and allows the integration of the Carlist military into the regular royal army.

The most favored personage was

General Espartero, known after his victory in Luchana as the ''"Espadón de Luchana"''. He obtained a great political and social presence and a noble title that turned him into

Grandees of Spain

Grandees of Spain ( es, Grandes de España) are the highest-ranking members of the Spanish nobility. They comprise nobles who hold the most important historical landed titles in Spain or its former colonies. Many such hereditary titles are held ...

, and he was

Duke of la Victoria. María Christina reigned until 1843, the year in which Princess Isabella was named of age and began to reign at the age of thirteen.

The regency of Maria Christina

The succession controversy

During the reign of

Philip V Philip V may refer to:

* Philip V of Macedon (221–179 BC)

* Philip V of France (1293–1322)

* Philip II of Spain, also Philip V, Duke of Burgundy (1526–1598)

* Philip V of Spain

Philip V ( es, Felipe; 19 December 1683 – 9 July 1746) was ...

, the exclusion of women in the line of succession had been established by the so-called

Salic Law

The Salic law ( or ; la, Lex salica), also called the was the ancient Frankish civil law code compiled around AD 500 by the first Frankish King, Clovis. The written text is in Latin and contains some of the earliest known instances of Old Du ...

. This norm had been revoked in 1789 by

Charles IV, by means of a decree that was never promulgated. On March 29, 1830, by means of the

Pragmatic Sanction

A pragmatic sanction is a sovereign's solemn decree on a matter of primary importance and has the force of fundamental law. In the late history of the Holy Roman Empire, it referred more specifically to an edict issued by the Emperor.

When used ...

,

Ferdinand VII elevated it to the rank of law. This was not an obstacle, however, for

Carlos Maria Isidro, Ferdinand's brother, to claim his rights to the

Spanish throne. Ferdinand VII had foreseen this controversy, and, wanting the throne for his first-born daughter, the future

Isabella II

Isabella II ( es, Isabel II; 10 October 1830 – 9 April 1904), was Queen of Spain from 29 September 1833 until 30 September 1868.

Shortly before her birth, the King Ferdinand VII of Spain issued a Pragmatic Sanction to ensure the successi ...

, he appointed his wife

Maria Christina as

Regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

, banishing his brother Carlos for refusing to recognize Isabella as heir.

Before the death of the King, the future Regent had managed to separate the military supporters of Carlos from the headquarters of the army and had guaranteed the support of the liberals in exile, as well as that of

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

. Nevertheless, Carlos proclaimed himself King of Spain on October 1, 1833, with the name of Carlos V; he had the express support of the

Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

crown, then in the hands of D. Miguel I, and the complicit silence of

Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

,

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

and

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

. The Spanish troops invaded Portugal in an attempt to punish the support to

Carlism

Carlism ( eu, Karlismo; ca, Carlisme; ; ) is a Traditionalist and Legitimist political movement in Spain aimed at establishing an alternative branch of the Bourbon dynasty – one descended from Don Carlos, Count of Molina (1788–1855) – ...

but with the mediation of England, Carlos was exiled to Great Britain, from where he would escape in 1834 to appear between

Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

and the

Basque Country and lead the Carlist War.

The first cabinets

In 1832,

Francisco Cea Bermúdez

Francisco de Paula de Cea Bermúdez y Buzo (28 October 1779, in Málaga – 6 July 1850, in Paris) was a Spanish politician and diplomat who served twice as Prime Minister of Spain.

Biography

A successful businessman, he was sent in 1810 by t ...

had been appointed

President of the Council of Ministers

The President of the Council of Ministers (sometimes titled Chairman of the Council of Ministers) is the most senior member of the cabinet in the executive branch of government in some countries. Some Presidents of the Council of Ministers are th ...

, linked to the most right wing of the moderates, who initiated timid administrative reforms but lacked the capacity and interest to facilitate the incorporation of many former enlightened and liberal members into the new model of economic and political development. Among the reforms of the cabinet of Cea Bermúdez, a

new division of Spain into provinces, promoted by the Secretary of State for Public Works,

Javier de Burgos

Francisco Javier de Burgos y del Olmo (22 October 1778—22 January 1848) was a Spanish jurist, politician, journalist, and translator.

Early life and career

Born in Motril, into a noble but poor family, he was destined for a career in the ...

, stood out, aimed at improving the administration, which, with some adjustments, is still in place today. The lack of harmony between economic and political

liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

and the Government led the Regent to dismiss Cea Bermúdez and to the appointment of

Martínez de la Rosa as the new president, in January 1834. The new president had to face the Carlist War, initiated by the supporters of the pretender in the

Basque Country,

Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

,

Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

and

Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to sou ...

fundamentally.

Martínez de la Rosa, who had returned from exile, tried to implement a reform of the

clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

and promulgated the

Royal Statute in 1834. In the form of a charter, it disguised the liberal spirit so as not to upset the followers of the

Ancien Régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for "ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

, leaving it unclear whether national sovereignty resided in the

King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

or in the

Cortes

Cortes, Cortés, Cortês, Corts, or Cortès may refer to:

People

* Cortes (surname), including a list of people with the name

** Hernán Cortés (1485–1547), a Spanish conquistador

Places

* Cortes, Navarre, a village in the South border of N ...

. The political equilibrium that this indeterminacy implied ended up not satisfying either one or the other. At the same time, the climate of confrontation intensified due to the intrigues of the Regent against the liberals and a

cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

epidemic

An epidemic (from Ancient Greek, Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of patients among a given population within an area in a short period of time.

Epidemics ...

that devastated Spain from south to north, generating the hoax that the

Church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* Chris ...

had poisoned the wells and canals that supplied

Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

with drinking water. Assaults on convents and churches were not long in coming. Harassed by both sides and unable to govern, Martínez de la Rosa resigned in June 1835.

The Royal Statute of 1834

The Carlist War forces

María Christina to transform the regime in order to remain on the throne. This change consists of granting powers to the liberals, with which it happens that the wife of the most absolutist Spanish king is the one who opens the way to

liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

.

In 1832,

Ferdinand VII recovers from an illness and appoints a new cabinet led by

Cea Bermudez, who governs until 1834 and carries out some reforms, quite conservative and directed by the king. The reforms are not well received neither by the absolutists nor by the liberals.

After the death of Fernando VII in 1833, several people close to the queen insinuated the need for a new Cortes and a new government, although later Maria Christina only appointed a new government under

Francisco Martínez de la Rosa

Francisco de Paula Martínez de la Rosa y Cornejo (March 10, 1787 – February 7, 1862) was a Spanish statesman and dramatist and the first prime minister of Spain to receive the title of ''President of the Council of Ministers''.

Biography

He ...

, who headed a moderate liberal government that should create a constitutional framework acceptable to the Crown. The progressives did not support Martínez de la Rosa, who was nicknamed "''Rosita la pastelera''" (Rosy the baker woman). Although Martínez de la Rosa may seem conservative, at the time he was a real revolution, since the monarchy renounces the monopoly of power. The Royal Statute is also a kind of compromise between

monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy) ...

and

liberals to thank them for their support during the war.

In practice the Royal Statute gives the Crown a great margin of action, since it directly appoints many deputies in the Cortes and the rest are elected only by the richest. The executive power belongs to the Queen and the legislative power belongs to the Queen and the Cortes. Liberal illusions collapse when they see the few concessions that the Crown gives them.

The Royal Statute establishes two chambers. In one are the non-elected representatives, the

Grandees of Spain

Grandees of Spain ( es, Grandes de España) are the highest-ranking members of the Spanish nobility. They comprise nobles who hold the most important historical landed titles in Spain or its former colonies. Many such hereditary titles are held ...

, who enter the Cortes directly. This chamber of non-elected representatives is the ''Estamento de Próceres''

(House of Peers). The other chamber, of deputies elected under census suffrage, is the ''Estamento de Procuradores''. They are only elected by about 16,000 men. The Royal Statute establishes that the Cortes vote taxes but does not give them the legislative initiative without the support of the Crown, which also has the executive power.

The progressives did not give up and used legal loopholes in the Royal Statute to make reforms. They were favored by the bad results of the liberals in the first years of the Carlist War, which forced María Cristina to make concessions. Among the progressive reforms are the approval of some rights of the individual (

freedom

Freedom is understood as either having the ability to act or change without constraint or to possess the power and resources to fulfill one's purposes unhindered. Freedom is often associated with liberty and autonomy in the sense of "giving on ...

, equality,

property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, r ...

, judicial independence and ministerial responsibility). In the end, the progressives put more and more pressure on María Cristina, until in 1835 the regent appointed a progressive liberal government.

The momentum of the liberals and the coming to power of the progressives

The progressives came to power through

insurrection

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

, with revolts throughout the summer of 1835 led by the Juntas and the Militias. Given the

anarchy

Anarchy is a society without a government. It may also refer to a society or group of people that entirely rejects a set hierarchy. ''Anarchy'' was first used in English in 1539, meaning "an absence of government". Pierre-Joseph Proudhon adopted ...

of the country, the Queen Regent was forced to appoint a progressive government, led by

Juan Álvarez Mendizábal

Juan Álvarez Mendizábal (born ''Juan Álvarez Méndez''; 25 February 1790 – 3 November 1853), was a Spanish economist and politician who served as Prime Minister of Spain from 25 September 1835 to 15 May 1836.

Biography

He was born to Rafae ...

, who quickly initiated a series of reforms that would lead

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

to become a more modern state.

The first objective of Mendizábal is to obtain money to increase the military troops of the liberals and to pay off the

public debt

A country's gross government debt (also called public debt, or sovereign debt) is the financial liabilities of the government sector. Changes in government debt over time reflect primarily borrowing due to past government deficits. A deficit oc ...

that the State had contracted with those who had invested in the State. Mendizábal's solution is the

confiscation

Confiscation (from the Latin ''confiscatio'' "to consign to the ''fiscus'', i.e. transfer to the treasury") is a legal form of seizure by a government or other public authority. The word is also used, popularly, of spoliation under legal forms, o ...

of the goods of the regular clergy and their sale, although the privileged estates are opposed and pressure María Cristina to dismiss Mendizábal. The queen agrees and throws Mendizábal out, but there is another violent uprising in the summer of 1836 to bring back a progressive government: the Mutiny of

''La Granja''. A new progressive government is created in which Mendizábal is only

Minister of Finance.

Progressive Reforms (1835-1837)

The great protagonist is Mendizábal. In 1823, after the

Liberal Triennium, he had gone into exile. During his exile in

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

he came into contact with the most liberal ideas. He has a new legal conception of property law based on the theories of

Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——— ...

and

capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, priva ...

theories. According to Mendizábal, to make

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

a liberal country, economically and politically speaking, the following steps had to be taken: the elimination of the seigniorial regime, the dissociation of the lands (ending the ''

majorat

''Majorat'' () is a French term for an arrangement giving the right of succession to a specific parcel of property associated with a title of nobility to a single heir, based on male primogeniture. A majorat (fideicommis) would be inherited by th ...

''), and the ecclesiastical and civil confiscation. Then the agricultural revolution could be carried out, with an increase in yields that would produce a surplus to invest in industry.

The seigniorial regime is eliminated in August 1837. The lords lose jurisdiction, but retain ownership of the land if they can prove that it is theirs. The seigniories are converted into capitalist holdings. The entailed estate is also eliminated, so many nobles improve their economic situation by selling land.

The most important is the ecclesiastical confiscation, which is carried out by means of the "Law of the vote of confidence", to make decisions on the war without the need to decide them in the Cortes. The confiscation is carried out by means of a decree without debate in the Cortes. Mendizábal took the opportunity to reform the regular clergy, with two decrees.

The first, of February 1836, is the "Decree of Extinction of the Regulars", which establishes the universal elimination of the orders of the regular male clergy. Only the missionary colleges and the hospitaller orders were saved. With respect to the feminine regular clergy, the suppression of convents is decreed and, in some, a maximum community of twenty nuns is fixed. In addition the coexistence of two convents of the same order within the same population center is prohibited; and it is also prohibited to admit novices and that the brothers are priests. Those who were priests are now parish priests of the secular clergy, and the lay brothers are left in the civil society, without compensation. All the possessions of the eliminated and reformed orders become national property.

The second decree, of March 1836, is the "Decree of sale of national goods". Mendizábal argues that it solves the problem of the Treasury by saving public debt; it justifies a socioeconomic reform based on the free market, promoting individual interest; and it says that this sale of goods would create a broad group of support for the ''Isabellin'' cause.

After this decree, the system of sale of national property is established. The installment sale system, which is the only possibility for the colonists to become owners, is rejected; and the

public auction

In public relations and communication science, publics are groups of individual people, and the public (a.k.a. the general public) is the totality of such groupings. This is a different concept to the sociological concept of the ''Öffentlichkei ...

system is approved, in which only the richest participate. The higher the bidding, the more the public debt is released.

All this reforming action was accompanied by a series of laws that ensured the

free market

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any o ...

. To this end, freedom is given in the form of land exploitation and free circulation of agricultural and industrial goods; the rights of the ''

Mesta

The ''Mesta'' () was a powerful association protecting livestock owners and their animals in the Crown of Castile that was incorporated in the 13th century and was dissolved in 1836. Although best known for its organisation of the annual migrat ...

'' are eliminated, among which are those of free passage and free grazing; permits are given for fencing off farms; freedom is given in land leases; freedom of storage and price (controlled only by supply and demand) are given.

The liberals felt strong and mobilized in protest demonstrations throughout the peninsula, which on many occasions turned into serious altercations. The press, with a markedly progressive tendency, did not spare the government from criticism and was in favor of a more

democratic system, with a greater role for

parliamentarism

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

. The Regent, however, offered the Head of Government to

José María Queipo de Llano, who, three months after accepting, presented his resignation because of the violent clashes that took place in

Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

and an uprising that formed revolutionary

juntas

A military dictatorship is a dictatorship in which the military exerts complete or substantial control over political authority, and the dictator is often a high-ranked military officer.

The reverse situation is to have civilian control of the m ...

similar to those of the

War of Independence

This is a list of wars of independence (also called liberation wars). These wars may or may not have been successful in achieving a goal of independence.

List

See also

* Lists of active separatist movements

* List of civil wars

* List of o ...

period. These juntas joined the

National Militia and took control of different provinces. The revolutionaries presented the Regent with a list of conditions in which they demanded an enlargement of the Militia, freedom of the press, a revision of the electoral regulations that would allow more heads of families to vote, and the convocation of the Cortes Generales.

Maria Christina

Maria Christina felt obliged to grant the government to

Mendizábal, in an attempt to alleviate the serious crisis and to make a gesture to the progressives. Aware of the situation, the new president reached an agreement with the liberals: the revolutionary juntas were to be dissolved and integrated into the administrative organization of the State, within the

provincial deputation, in exchange for the political and economic reforms that he undertook to carry out. He obtained extraordinary powers from the Cortes to carry out reforms in the system that took the form of a substantial modification of the

public treasury and the tax system to guarantee a healthy State capable of meeting its obligations, meeting its loans and obtaining new

credit

Credit (from Latin verb ''credit'', meaning "one believes") is the trust which allows one party to provide money or resources to another party wherein the second party does not reimburse the first party immediately (thereby generating a debt), ...

s, in addition to the

confiscation

Confiscation (from the Latin ''confiscatio'' "to consign to the ''fiscus'', i.e. transfer to the treasury") is a legal form of seizure by a government or other public authority. The word is also used, popularly, of spoliation under legal forms, o ...

of a large part of the assets of the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, with the aim of making it possible to bring hitherto unproductive goods into commerce.

Among the measures that Mendizábal intended to carry out was a wide remodeling of the army, which included as first step a change in the high commands, very linked to the most reactionary sectors. Although the military troops were increased to 75,000 new men and a greater contribution of 20 million pesetas was destined to the Carlist War, the reorganization did not please the Regent, who because of it lost authority in the

armed forces

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

. Mendizábal was dismissed after a campaign of discredit,

Francisco Javier de Istúriz was appointed President of the Council of Ministers, a progressive who had returned from exile and had evolved towards much more moderate positions and contrary to the confiscation process, positioning himself as a man of the Regent's clique. After dissolving the Cortes in search of new ones that would legitimize him and support a constitution different from the Royal Statute, even more conservative, his wishes were abruptly interrupted by the Mutiny of

La Granja de San Ildefonso

San Ildefonso (), La Granja (), or La Granja de San Ildefonso, is a town and municipality in the Province of Segovia, in the Castile and León autonomous region of central Spain.

It is located in the foothills of the Sierra de Guadarrama mounta ...

, which sought and obtained that the Regent reinstated the

Constitution of 1812

The Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy ( es, link=no, Constitución Política de la Monarquía Española), also known as the Constitution of Cádiz ( es, link=no, Constitución de Cádiz) and as ''La Pepa'', was the first Constituti ...

and repealed the Statute. Istúriz resigned on August 14, 1836, barely three months after his appointment.

The new President of the Government was

José María Calatrava, who appointed Mendizábal as

Minister of Finance

A finance minister is an executive or cabinet position in charge of one or more of government finances, economic policy and financial regulation.

A finance minister's portfolio has a large variety of names around the world, such as "treasury", " ...

, in a continuist line. He took advantage of this to conclude the confiscation process and the suppression of the

tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more r ...

s. Calatrava promoted a social policy that allowed him to approve the first law in Spain that regulated and recognized the

freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic News media, media, especially publication, published materials, should be conside ...

. But the most important work was the adaptation of the

Constitution of 1812

The Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy ( es, link=no, Constitución Política de la Monarquía Española), also known as the Constitution of Cádiz ( es, link=no, Constitución de Cádiz) and as ''La Pepa'', was the first Constituti ...

to the new reality to which the Regent had committed herself by Royal Decree during the Mutiny of La Granja, with the approval of the

Constitution of 1837.

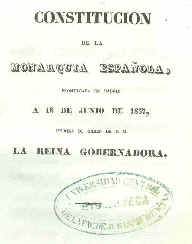

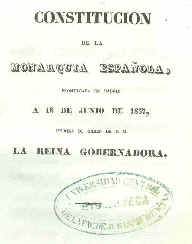

Constitution of 1837

After the Mutiny of

La Granja, the progressive government convened an extraordinary constituent Cortes, which had two options: to reform the

Constitution of 1812

The Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy ( es, link=no, Constitución Política de la Monarquía Española), also known as the Constitution of Cádiz ( es, link=no, Constitución de Cádiz) and as ''La Pepa'', was the first Constituti ...

or to create a new one. This would give rise to the

Constitution of 1837, which would lead to a new political system until 1844. In addition, the reforms it proposes give rise to a class society. The progressive party, "direct heir" of the ''doceañistas'', proposes the reform of the Constitution of 1812, but in reality gives birth to a new Constitution that wants to be of consensus and therefore acceptable to the moderates. This moderantism is seen at the moment of deciding the form of government, because they choose a

constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

of a doctrinaire liberal character: the executive role of the Crown is reinforced. They only agree with the ''doceañistas'' in the proclamation of national sovereignty, from which the constitution arises without the Crown acting. But the affirmation of the principle of national sovereignty is not made in the articles, as was the case in the Constitution of 1812, but appears in the preamble.

The Constitution of 1837 established a

bicameral Cortes: the

Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, appointed by the Queen; and the

Lower House

A lower house is one of two Debate chamber, chambers of a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the upper house. Despite its official position "below" the upper house, in many legislatures worldwide, the lower house has co ...

, elected by census suffrage. The Crown can dissolve the Cortes, in which it acts as moderator, and veto laws. It is the first power of the State, although its powers are limited by the Cortes, which are on a lower plane.

The reasons that lead the progressives to make this constitution have given rise to a debate in

historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods of historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians ha ...

. One of the most widely followed ideas is that the progressives, with all the power, break the political exclusivism between progressives and moderates, create a transactional constitution, to accommodate the Crown. This theory considers the Constitution of 1837 as the precedent of the

Canovist Constitution of 1876. It is followed by Suanzes-Carpeña and Miguel de Artola.

Another idea of some historians is that exclusivism is accidental, and that the progressives did not dare to propose a system other than

constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

. They thought neither of a parliamentary monarchy nor of a

republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

. This second idea is defended by

Javier Tusell Javier Tusell Gómez (26 August 1945, Barcelona - 8 February 2005, Barcelona) was a Spanish historian, writer and politician who served as a professor of modern history at the National University of Distance Education (UNED).[moderate

Moderate is an ideological category which designates a rejection of radical or extreme views, especially in regard to politics and religion. A moderate is considered someone occupying any mainstream position avoiding extreme views. In American ...]

and the

progressive parties defend the same thing, they are the same, and that the only difference between them is the pace of reforms. As for the social model they defend, it is a mesocratic Spain, of capitalist owners and free market.

Apart from this debate on the Constitution of 1837, the great problem of liberalism is the economic backwardness of the country, so the middle class is very weak. Liberalism has enemies on the right, the absolutists; and on the left, the supporters of a social revolution. In the meantime, the only thing that interests the liberals is to maintain what they have achieved. Progressives and moderates knew that order could not be maintained by an insecure parliament with many alternations, so they opted to strengthen the executive power, which offered two possibilities: an authoritarian regime in the hands of a military man or to strengthen the Crown. Within the second option, the progressives contemplate a monarchy with all the powers, but they want someone they can control as king.

Although in principle it was an attempt to reform the Constitution of 1812, the Constitution of 1837 was a completely new Constitution, drawn up on the basis of a certain consensus that sought to overcome the discussion between progressives and moderates on the question of national sovereignty. The text, very short, recognized the

legislative power

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country or city. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers of government.

Laws enacted by legislatures are usually known as p ...

of the Cortes —in a bicameral system with the

Congress of Deputies

The Congress of Deputies ( es, link=no, Congreso de los Diputados, italic=unset) is the lower house of the Cortes Generales, Spain's legislative branch. The Congress meets in the Palacio de las Cortes, Madrid, Palace of the Parliament () in Ma ...

and the Senate— together with the King, to whom corresponded the prerogatives of the

Head of State

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and ...

and the

executive power

The Executive, also referred as the Executive branch or Executive power, is the term commonly used to describe that part of government which enforces the law, and has overall responsibility for the governance of a state.

In political systems ba ...

, which he later delegated to the Presidency of the Council of Ministers, but reserving great maneuvering capacity, such as the dissolution of the Chambers. The text protected freedom of the press, among other individual rights.

The Carlists at the gates of Madrid

The Constitution was drawn up while the

Carlists had taken

Segovia

Segovia ( , , ) is a city in the autonomous community of Castile and León, Spain. It is the capital and most populated municipality of the Province of Segovia.

Segovia is in the Inner Plateau (''Meseta central''), near the northern slopes of th ...

and were at the gates of

Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

. Azara resigned shortly after the Constitution was approved.

Since 1833, the Carlists had been at war against the

Christinos

The Christinos (Spanish: Cristinos) (sometimes called the ''Isabellinos'' or the ''Liberales'') was the name for the supporters of the claim of Isabel II to the throne of Spain during the First Carlist War. The Christinos drew their name from Mar ...

. They had made themselves strong in the

Basque Country,

Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

and

Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

, fundamentally, with an initial support of some 70,000 men, although there were far fewer of them in arms. On November 14, 1833, the Juntas of

Alava and

Biscay

Biscay (; eu, Bizkaia ; es, Vizcaya ) is a province of Spain and a historical territory of the Basque Country, heir of the ancient Lordship of Biscay, lying on the south shore of the eponymous bay. The capital and largest city is Bilbao.

B ...

named

Tomás de Zumalacárregui

Tomás de Zumalacárregui e Imaz (Basque: Tomas Zumalakarregi Imatz; 29 December 178824 June 1835), known among his troops as "Uncle Tomás", was a Spanish Basque officer who lead the Carlist faction as Captain general of the Army during the Firs ...

head of their armies. The Christino army counted at that time about 115,000 men, although only about 50,000 were capable of fighting. In the future, about half a million men had to be mobilized to face the Carlist troops victoriously. The

Infante Don Carlos, escaped from his English exile, settled between

Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

and the

Basque Country, and from there he directed the conflict, establishing the capital in

Estella

Estella may refer to:

People

* Diego de Estella (1524–1578)

* Estella Sneider (born 1950)

*Estella Warren (born 1978), Canadian actress

*Estella, the ''nom de guerre'' of Italian labor leader Teresa Noce

Fictional

*Estella Havisham, a charact ...

.

After initial successes, Zumalacárregui lost the

Battle of Mendaza

The Battle of Mendaza was an early battle of the First Carlist War, occurring on December 12, 1834, at Mendaza, Navarre.

The Carlists had enjoyed a victory in the Battle of Venta de Echavarri in October and also the fruits of a raid on Navarre, ...

on December 12, 1834, and retreated until a new incursion in the spring of 1835 that forced the Regent's followers to position themselves beyond the

Ebro River

, name_etymology =

, image = Zaragoza shel.JPG

, image_size =

, image_caption = The Ebro River in Zaragoza

, map = SpainEbroBasin.png

, map_size =

, map_caption = The Ebro ...

. During the siege of Bilbao on June 15 of that year, Zumalacárregui suffered battle wounds that caused his death days later. In the summer of 1835, the ''Isabellinos'' under the command of

General Fernández de Córdova tried to isolate the Carlists in the north but only managed to maintain control of the most important cities.

The death of Zumalacárregui caused a stabilization of the fronts, except for the incursion of 1837 to the gates of

Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

.

General Baldomero Espartero was in charge of leading the troops loyal to the Regent and avoiding the onslaught of the

Royal Expedition that approached

Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

, until August 29, 1839, when he signed peace with the Carlist general

Rafael Maroto

Rafael Maroto Yserns (October 15, 1783 – August 25, 1853) was a Spanish general, known both for his involvement on the Spanish side in the wars of independence in South America and on the Carlist side in the First Carlist War.

Childhood a ...

in what is known as the ''Abrazo de Vergara'' (

Embrace of Vergara

The Convention of Vergara ( es, Convenio de Vergara, eu, Bergarako hitzarmena), entered into on 31 August 1839, was a treaty successfully ending the major fighting in Spain's First Carlist War. The treaty, also known by many other names includi ...

).

The contending political formations

The

Progressive Party defended a national sovereignty that resided only in the

Cortes Generales

The Cortes Generales (; en, Spanish Parliament, lit=General Courts) are the bicameral legislative chambers of Spain, consisting of the Congress of Deputies (the lower house), and the Senate (the upper house).

The Congress of Deputies meets ...

, which put them in opposition to the monarchist thesis, although their intention was not the establishment of a

Republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

. He organized a

National Militia, much contested by the moderates who saw in it the end of the army of the notables. In economic matters, they relied on the theses of

Mendizábal and

Flórez Estrada, with the confiscation processes, the abolition of the ''

majorat

''Majorat'' () is a French term for an arrangement giving the right of succession to a specific parcel of property associated with a title of nobility to a single heir, based on male primogeniture. A majorat (fideicommis) would be inherited by th ...

'' and the opening of trade and free trade.

In 1849, the

Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

was formed, which was more ambitious than the progressives and sought

universal manhood suffrage

Universal manhood suffrage is a form of voting rights in which all adult male citizens within a political system are allowed to vote, regardless of income, property, religion, race, or any other qualification. It is sometimes summarized by the slog ...

as opposed to

census suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

, the legalization of the incipient

workers' organizations and a fair distribution of land for farmers, since confiscation had changed hands but had not brought land to the peasants.

The

moderates

Moderate is an ideological category which designates a rejection of radical or extreme views, especially in regard to politics and religion. A moderate is considered someone occupying any mainstream position avoiding extreme views. In American ...

presented themselves as those who contained the liberals in their eagerness to destroy the monarchy and the

Ancien Régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for "ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

. Its members were mostly

nobles

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteristi ...

,

aristocrats

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word' ...

, high officials,

lawyer

A lawyer is a person who practices law. The role of a lawyer varies greatly across different legal jurisdictions. A lawyer can be classified as an advocate, attorney, barrister, canon lawyer, civil law notary, counsel, counselor, solic ...

s and members of the Court and the

clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

. They claimed a concept of national sovereignty shared between the King and the Cortes with alleged "historical rights" and "ancient customs".

The moderate triennium (1837-1840)

Whether it was due to the Carlist offensive or to the very weakness of the political parties or to both phenomena,

Calatrava's succession brought three men from the most moderate wing of liberalism to the Presidency of the Council of Ministers in less than a year.

The first was

Eusebio Bardají Azara, who acceded after the resignation of

Espartero

Baldomero Fernández-Espartero y Álvarez de Toro (27 February 17938 January 1879) was a Spanish marshal and statesman. He served as the Regent of Spain, Regent of the Realm, three times as Prime Minister of Spain, Prime Minister and briefly ...

, who preferred to continue the military campaign, and obtained even more prestige when he came down from

Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

with his men to defend the capital from the Carlist troops of General Juan Antonio de Zaratiegui, whom he defeated. Azara resigned, dissatisfied with the position of the Regent, who tried by all means to win the sympathies of Espartero's men. He was followed by

Narciso de Heredia and

Bernardino Fernández de Velasco. However, on December 9, 1838,

Evaristo Pérez de Castro

Evaristo Pérez de Castro y Colomera (26 October 1778, in Valladolid – 28 November 1849, in Madrid) was a Spanish politician and diplomat who served as Prime Minister of Spain from 3 February 1839 to 18 July 1840, and held other important offi ...

was appointed. The new president established reforms in local administration that allowed a certain level of state

interventionism, and at the same time tried to reconcile the most negative aspects of the confiscation of

Mendizábal with the

Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of Rome ...

, especially suspicious of the Spanish Crown since the death of

Fernando VII.

The "revolution of 1840" and the end of the regency of Maria Christina

The idea of a peaceful alternation in power between moderates and progressives supported by the

Constitution of 1837 was frustrated when the moderate government of

Evaristo Pérez de Castro

Evaristo Pérez de Castro y Colomera (26 October 1778, in Valladolid – 28 November 1849, in Madrid) was a Spanish politician and diplomat who served as Prime Minister of Spain from 3 February 1839 to 18 July 1840, and held other important offi ...

presented a bill for the Local Government Law in which the appointment of the mayor corresponded to the government which would choose him from among the elected councilors, which, according to the progressives, was contrary to article 70 of the Constitution (''"For the government of the towns there will be Local Governments appointed by the neighbors to whom the law grants this right"''), so the progressives resorted to popular pressure during the debate of the law —a riot in

Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

ended with the invasion of the tribunes of the

Congress of Deputies

The Congress of Deputies ( es, link=no, Congreso de los Diputados, italic=unset) is the lower house of the Cortes Generales, Spain's legislative branch. The Congress meets in the Palacio de las Cortes, Madrid, Palace of the Parliament () in Ma ...

from where they shouted and insulted the moderate deputies— and, when the law was approved without admitting their amendments, they opted for withdrawal and left the Chamber, thus questioning the legitimacy of the Cortes. Immediately, the progressives began a campaign so that the regent Maria Christina would not sanction the law under the threat of not obeying it —that is, under the threat of rebellion— and when they saw that the regent was willing to sign it, they addressed their petitions to

General Baldomero Espartero, the most popular figure of the moment after his triumph in the

First Carlist War

The First Carlist War was a civil war in Spain from 1833 to 1840, the first of three Carlist Wars. It was fought between two factions over the succession to the throne and the nature of the Spanish monarchy: the conservative and devolutionist ...

and who was closer to

progressivism

Progressivism holds that it is possible to improve human societies through political action. As a political movement, progressivism seeks to advance the human condition through social reform based on purported advancements in science, tec ...

than to moderantism, to prevent the promulgation of that law contrary to the "spirit of the Constitution of 1837".

The radical opposition of the progressives to the Local Government Law —to the point that it made them abandon the "legal way" to opt for the "revolutionary way"— was due, according to Jorge Vilches, to the importance of the figure of the mayor in the elaboration of the electoral census —the local government was the one that issued the electoral ballots— and in the organization, direction and composition of the

National Militia, which made the progressives fear that their chances of gaining access to the government through elections would be practically nil, in addition to the fact that the militia, whose existence for the progressives was essential for the "vigilance of the rights of the people," would be placed in the hands of the moderates.

The Regent was aware that the system was in a serious crisis and moved to

Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

on a supposed vacation with

Isabella

Isabella may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Isabella (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Isabella (surname), including a list of people

Places

United States

* Isabella, Alabama, an unincorpor ...

to alleviate the dermatological ailments of the girl and met with

Espartero

Baldomero Fernández-Espartero y Álvarez de Toro (27 February 17938 January 1879) was a Spanish marshal and statesman. He served as the Regent of Spain, Regent of the Realm, three times as Prime Minister of Spain, Prime Minister and briefly ...

. This one, to accept the Presidency of the Council of Ministers, demanded that Maria Christina did not sanction the Local Government Law, so when on July 15, 1840, he signed the law, because to give back in something that already had announced publicly that it was going to do would suppose the submission to Espartero, this one presented him the resignation of all his degrees, employments, titles and decorations. The government of Pérez de Castro resigned on July 18 and was replaced on August 28, after three fleeting governments, by another moderate government presided over by Modesto Cortázar.

In

Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

and

Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

the altercations between moderates and progressives, between supporters of the Regent and

Espartero

Baldomero Fernández-Espartero y Álvarez de Toro (27 February 17938 January 1879) was a Spanish marshal and statesman. He served as the Regent of Spain, Regent of the Realm, three times as Prime Minister of Spain, Prime Minister and briefly ...

took place. In this situation